WHY

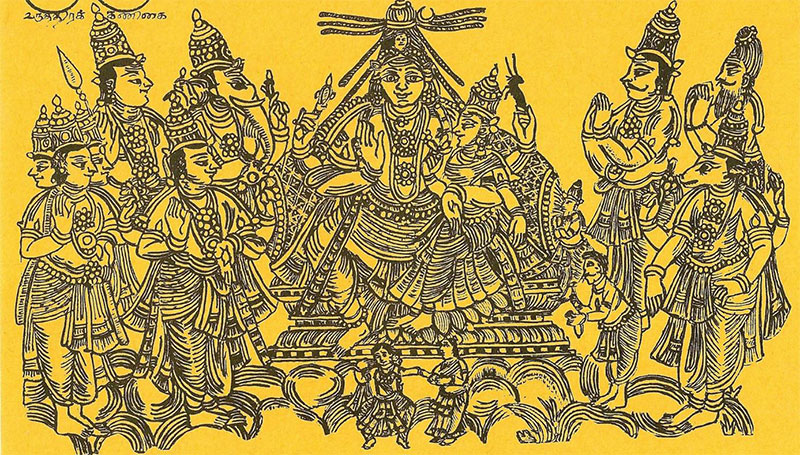

Dasi Attam - dance of the devadasis

Until the XXth century music and dance belonged to the culture of royal courts and rituals performed in Hindu temples. These performing arts constituded the hereditary right of professional dancers and musicians. They can trace their antecedents back to the first century C.E. but became generally known as Devadasis –servants of god. When Independent India forbade in 1947 the ritual marriage between women and gods, goddesses or religious synonyms, devadasis lost their traditional rights of labour, housing, lands and maintenance in temples, leaving many of them destitute.

This time-slot preferred a socially neutral name ’Bharata Natyam’ to an art that for centuries had been know as Dasi Attam, Chinna Melam or Sadir indicating the social background of its professional performers. This choice facilitated a shift to leisured performers who devised crucial adaptations to suit a global exposure and marginalization of the local Dasi Attam.

Tanjore Margam

The central focus of the Marapu curriculum is to gradually master one full concert-suite called Margam. This is the traditional format of a classical South Indian ’dance-concert’. It dates back to the forebears of Smt.T.Balasaraswati (1918-1984) whose family was attached to the royal court of Tanjore for over seven generations.

Four brothers were the master minds behind the codification of this format and its training curriculum: Ponniah, Chinniah, Shivanandam and Vadivelu formed together the Tanjore Quartet (18th Cent.CE); their heritage continues in Smt.T. Balasaraswati’s style through her teacher Kandappa Pillai (1899-1942) and his son Ganesan Pillai (1924-1987).

Devadasi Murai

The Devadasi Act of November 27, 1947 was the outcome of centuries unease over this matrilineal community of ritual specialists and sophisticated artists in both Western but decisevely so Indian society. Gradual collapse of the socio-economic infrastructures in temples and royal courts worsened the fate of the devadasis.

The so-called Hindu-Renaissance did not look favourably upon their heritage; it rather preferred to project a ’spiritual character’ of Hinduism over the more concrete forms of worship as practised in temple and village shrines.

Appropriation of devadasi arts has been a long and painful process for those who held ritual and customary rites to perform in temples, courts and social rites of passage. Few devadasis could make the transition from the temple and court to the western style proscenium stage. In 1977 Smt.P. Ranganayaki (1914-2005), devadasi at the Shri Subrahmanya temple in Tiruttani, accepted Saskia as her student and legitimate heir of her family tradition in ritual music and dance.